What happens when you take two seemingly disparate subjects and examine them in light of each other? What insights will be gained? What revelations will unfold? This is exactly the premise of Juan Pimentel’s fascinating 2010 book The Rhinoceros and the Megatherium: An Essay in Natural History, originally published in Spanish and recently translated into English by Peter Mason and published by Harvard University Press in 2017.

Pimentel is an Associate Professor of History of Science at the Institute of History (CSIC) in Madrid, and in this book juxtaposes two seemingly unrelated episodes in the history of zoology — the arrival in Europe of the first Indian rhinoceros (nicknamed Ganda), and the first discovery of prehistoric vertebrate fossil bones, of the megatherium.

When the first Indian rhinoceros arrived in Portugal via boat in 1515, it was much more than an exotic animal. It was received as a living embodiment of the orient, and all that such a label entailed. Accordingly, the rhinoceros became a commodity, one that would play an important role in political gift-giving, which is not about generosity but power, as it was passed between governors and sultans, kings and popes.

Upon arriving in Portugal, the rhinoceros was pitted in gladiatorial combat against an (adolescent) elephant. While we may be aghast at such barbarity now, Pimentel is quick to note that this was not a simple blood sport.

Rather it was, incredibly, a scientific experiment. The fight was an attempt to test an assertion of the greatest naturalist of all antiquity, Pliny, who had maintained that the fearsome rhinoceros – which daily sharpened its great horn upon the stones – was the mortal enemy of the noble elephant. Needless to say, Ganda did not disappoint.

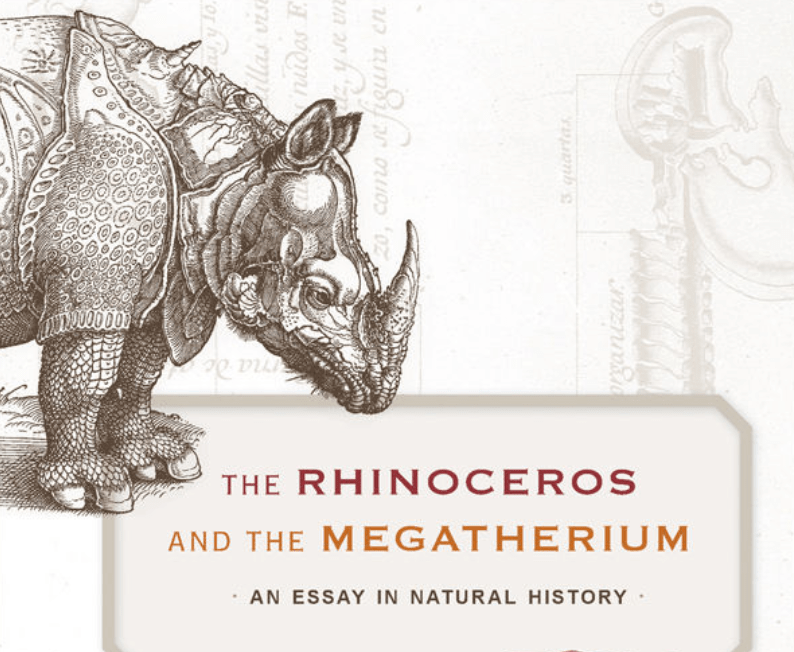

The rhinoceros was deemed priceless not only because of its rarity, but because it was alive and thus perishable, as all living things are. After Ganda died – tragically in a boating accident – it was immortalized as a woodcut by the acclaimed German artist Albrecht Dürer.

Dürer was an accomplished artist of nature, but it must be recognized that his etching of the rhinoceros is not the least bit realistic. With its heavy, overlapping, plate-like armor, chainmail-covered legs, and gnarled horn with a second unicorn-like protrusion erupting from its back, Dürer’s rhinoceros looks more like some kind of mammalian dragon, which Pimentel observes was probably intentional, since Pliny had written that other than the rhino, the animal which most consistently threatened the elephant was the dragon.

Despite its inaccuracy, Dürer’s illustration would go on to become one of the most iconic images of the Renaissance. This was not due to any kind of monopoly on images of rhinoceroses, as the artist Hans Burgkmair had also made an etching of the animal, one that was far more accurate than Dürer’s. But Dürer’s was more popular because it better conformed to people’s preexisting conception of what a rhinoceros was – or perhaps should be – and because Dürer made use of the latest printing technologies and succeeded in disseminating his image more widely.

If the rhinoceros succeeded in achieving fame due to being so far removed from western civilization geographically, then the second animal examined by Pimentel, the megatherium, accomplished the same feat by being even more far removed in terms of geologic time. When the bones of the megatherium were first discovered in 1787 in Luján, Buenos Aires, nothing like it was known outside of the realm of myth. It defied all preexisting categorical definitions.

Like Ganda, the first megatherium became the subject of political machinations, albeit of a different variety. The issue here was one of scientific and national prestige and recognition. Because the fossil remains had been discovered in South America, they were initially claimed by Spain. However the two naturalists, Jean Bautista Bru and Manuel Navarro, who were assigned to study the beast, were poorly equipped to do so. They were slow to publish their findings and got caught up in a controversy over allegations of academic plagiarism.

While this was going on, similar bones were found in a cave in West Virginia, and so Thomas Jefferson, who had a keen interest in American monsters, tried to claim the megatherium for the fledgling United States. But like Bru and Navarro, Jefferson was unsure of what kind of animal the megatherium might be. All three men thought it was possible the creature might have been some kind of huge cat!

It was finally France’s Georges Cuvier who would solve the mystery of the megatherium, declaring it a giant relative of today’s humble sloth. Ironically, Cuvier was the only one who had no hands-on experience with the fossils, his analysis being based entirely on drawings he was sent of the bones.

However, Cuvier had a superior knowledge of zoology, which he’d used to pioneer the discipline of comparative anatomy. Pimentel adds that Cuvier had a grand imagination which, for the father of paleontology, was more important than direct observation, which only gets you so far. Paleontologists can never see the subjects of their study; they can only imagine them.

For Pimentel, the real significance of the megatherium is how it helped bring about the revolutionary conceptualization of geological Deep Time, and the realization that the earth is millions upon millions of years old. But this leads him into what might be considered his book’s only serious pitfall — a very long digression in which he sketches out the history of the idea of Deep Time over the span of 165 pages, which is more space than allotted to either of the animal subjects of his book!

Readers who are familiar with the academic work of paleontological historian Martin Rudwick, or the more popular accounts of writer Riley Black, will undoubtedly feel a certain overwhelming sense of déjà vu here. But for those to whom this is new information, Pimentel does provide a highly readable and, when compared with the works of Rudwick, condensed history of the development of the idea of Deep Time.

While Ganda the rhinoceros and the first discovered megatherium were very different, they share certain striking similarities, the most important of which is how images of these two animals shaped how they were conceived and understood on both the scientific and popular level. As Pimentel writes in his conclusion, this is an important lesson, especially when considering the fact that so much of popular science is based on trusting what we have not seen for ourselves.

AIPT Science is co-presented by AIPT and the New York City Skeptics.

Join the AIPT Patreon

Want to take our relationship to the next level? Become a patron today to gain access to exclusive perks, such as:

- ❌ Remove all ads on the website

- 💬 Join our Discord community, where we chat about the latest news and releases from everything we cover on AIPT

- 📗 Access to our monthly book club

- 📦 Get a physical trade paperback shipped to you every month

- 💥 And more!

You must be logged in to post a comment.